The South China Sea, patrolled by American and Chinese naval forces and accounting for over one-fifth of global trade flows, is one of the world’s most volatile flashpoints.

Although cross-strait tensions between China and Taiwan receive the most attention, the Philippines increasingly bears the brunt of regional Chinese pressure.

In the past year alone, over 100 Chinese Coast Guard ships have entered Philippine waters weekly, repeatedly attacking Philippine military and fishing vessels by firing water cannons and intentionally colliding with them, resulting in severe injuries to Philippine sailors.

The Philippines is America’s only treaty ally in the South China Sea. Managing that alliance is vital not only to deter Chinese aggression but also as a litmus test for the credibility of American power.

As the US presidential election looms, Donald Trump and Kamala Harris offer opposing strategies for maintaining alliances.

Trump’s “America First” approach could undermine deterrence and push the Philippines closer to China. In contrast, Harris would likely maintain continuity and emphasize America’s alliance commitments, an approach that would reinforce allies’ confidence in US leadership and counter regional Chinese ambitions.

The Overlooked Crisis

Despite rising tensions between Beijing and Manila, the Taiwan issue dominates the conversation around South China Sea territorial disputes.

Yet, the Philippines is the only formal US treaty ally in the region facing consistent pressure from China, including encounters with military-grade lasers. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has clearly warned that an attack on Philippine interests or the loss of Philippine life would constitute an act of war.

Escalation is not in anyone’s interest. However, increased Chinese military activity inside the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone has prompted a US-Philippines response.

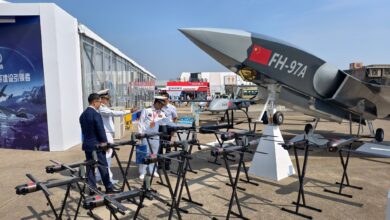

When the US and the Philippines recently expanded joint naval patrols, China ordered military officials to detain foreign nationals trespassing in Chinese-claimed waters. Even as Beijing built the world’s largest navy, the US has helped Manila advance its own maritime capabilities.

Fortifying the Alliance

The revitalization of US-Philippine relations is a model for alliance-based deterrence vis-à-vis China.

When Manila drew closer to Beijing under then-Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, the US-Philippine alliance reached a nadir. When Marcos departed from Duterte’s China policy, Joe Biden seized an opportunity to revamp cooperation and improve Manila’s security. He opened a training center for the Philippine Coast Guard and expanded US military operations to four new bases.

In an unprecedented move, the administration also deployed a US Coast Guard Fast Response Cutter to the island of Leyte following a skirmish between Philippine and Chinese military forces.

Most recently, Biden announced $500 million in additional military aid for Manila.

These policies have angered Beijing, prompted increased Chinese aggression, and probed Philippine resolve. However, they also reflect a long-term strategic approach aimed at countering China’s influence and preventing Beijing from goading a Manila bereft of American support.

If Manila were driven closer to Beijing, US interests would suffer, and Beijing could operate freely in the West Philippine Sea.

While few were paying attention, Biden strengthened the US-Philippine alliance more than any leader in modern American history. Still, Biden’s strategy of alliance-based deterrence faces significant challenges in the near term, particularly with the impending US presidential election.

Given the economic and military stakes, it is crucial to consider how the winning candidate could influence US deterrence efforts in the South China Sea and American credibility worldwide.

Trump: Round 2?

Manila ought to be worried about Trump’s agenda and priorities in the South China Sea. During his first term, Trump’s unpredictable nature and marked disdain for traditional alliances left America’s partners demanding a more collaborative approach.

If Trump continues to neglect the complexities of alliances, as he did by questioning US security commitments with Japan and vowing to end joint US-South Korean military exercises, an assertive China could increase attacks on Philippine ships and bring the region closer to war.

While Trump’s advisors have privately assured Manila’s envoy that he would uphold Washington’s current policy in the region, his past actions suggest, at best, a counter-productive approach to alliances.

Trump’s use of transactional language is well-documented and comes at the expense of US credibility. When Duterte ended a longstanding Visiting Forces Agreement with America late in Trump’s first term, US Secretary of Defense Mark Esper criticized the decision while Trump applauded the move, myopically asserting it would “save [America] a lot of money.” In July, Trump also made similar comments about Taiwan, suggesting it should “pay [the United States] for defense.”

To be fair, Trump’s first term included statements rejecting China’s claims in the South China Sea and promising to defend the Philippines if attacked.

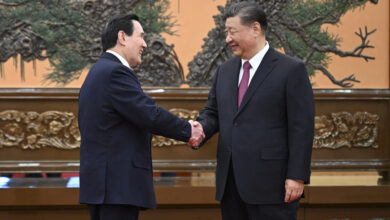

While Trump did rhetorically adhere to established commitments while in power, his transactional approach and affinity for strongmen — like the Philippines’ Duterte and China’s Xi Jinping — unnerve allies. This risks emboldening Xi, who has exploited Trump’s susceptibility to flattery to exacerbate alliance weaknesses and undermine US deterrence efforts.

Harris: Continuity or Uncertainty?

Harris is likely to sustain the core elements of Biden’s alliance-based deterrence strategy toward China given her advocacy for US leadership and strong alliances.

In the Indo-Pacific, she will leverage her regional experience, including having led the US delegation to ASEAN in 2023. In addition to hosting the first US-Japan-Philippines trilateral summit, Harris also met with Marcos five other times as Vice President, creating a strong basis for the personal rapport key to alliance maintenance.

She may also have the political capital in both Washington and Manila to build on the strategic gains made under Biden.

However, Harris may adapt Biden’s approach. Her evolving stance on the Israel-Hamas war, where she has become the administration’s lead advocate for a ceasefire, suggests that her geopolitical strategy may differ from Biden’s.

Moreover, during a transition in US leadership, Indo-Pacific allies will evaluate the new administration’s commitment to the region.

Harris’ foreign policy priorities may be revealed in her rhetoric on Ukraine and Israel, where she pledged ongoing support for Ukraine and urged Biden to express greater concern for Gaza’s humanitarian crisis. It is possible that a Harris administration may focus on managing these immediate conflicts, which could affect how attention and resources are allocated across global priorities.

Still, Harris remains firm in supporting Philippine sovereignty and rejecting China’s maritime claims. Since Biden’s policy in the South China Sea has proven effective, a Harris administration represents the best opportunity to continue and refine this alliance-based deterrence strategy. However, she must carefully navigate her policy shifts to avoid alienating the Philippines or sending the wrong message to allies.

The Future of US Credibility

Despite its low profile, the US-Philippines alliance is a key indicator of US leadership and reliability. The approach to managing this alliance highlights differences between Trump and Harris.

While Trump has a problematic track record with alliances, a Harris presidency would likely maintain the US-Philippines alliance and enhance deterrence against China.

Ultimately, the next election will not only shape US-Philippine relations but also test American credibility as an ally in the Indo-Pacific and globally. Should the US fail this test, it risks accelerating Beijing’s influence in the region and pushing China’s neighbors closer to Beijing.

Jason Hug is a joint Juris Doctor and Master in Public Policy candidate at Yale Law School and the Jackson School of Global Affairs.

Jason Hug is a joint Juris Doctor and Master in Public Policy candidate at Yale Law School and the Jackson School of Global Affairs.

Jason previously served as a US Army Intelligence Officer for five years. He was an Honor Graduate of the United States Military Academy, where he obtained a Bachelor of Science in Life Science.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Army, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Defense Post.

The Defense Post aims to publish a wide range of high-quality opinion and analysis from a diverse array of people – do you want to send us yours? Click here to submit an op-ed.