US withdrawal from INF treaty fires the starting pistol on a new arms race

Withdrawal from the a Cold War intermediate-range nuclear missile limitation treaty serves under-pressure US President Donald Trump in several ways, Dr Michelle Bentley argues

Following months of speculation, President Donald Trump confirmed that the U.S is withdrawing from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

The INF is a Cold War agreement, signed in 1987 by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev. The treaty prohibits nuclear missiles with a range of 500 to 5,500 km. It was negotiated after the U.S. and Russia both deployed shorter-range missiles in Europe during the 1980s – the American Pershing II and the Soviet SS-20 Saber. Military officials were concerned that the short flight time – six minutes – made these especially usable weapons that could easily trigger wider nuclear exchange.

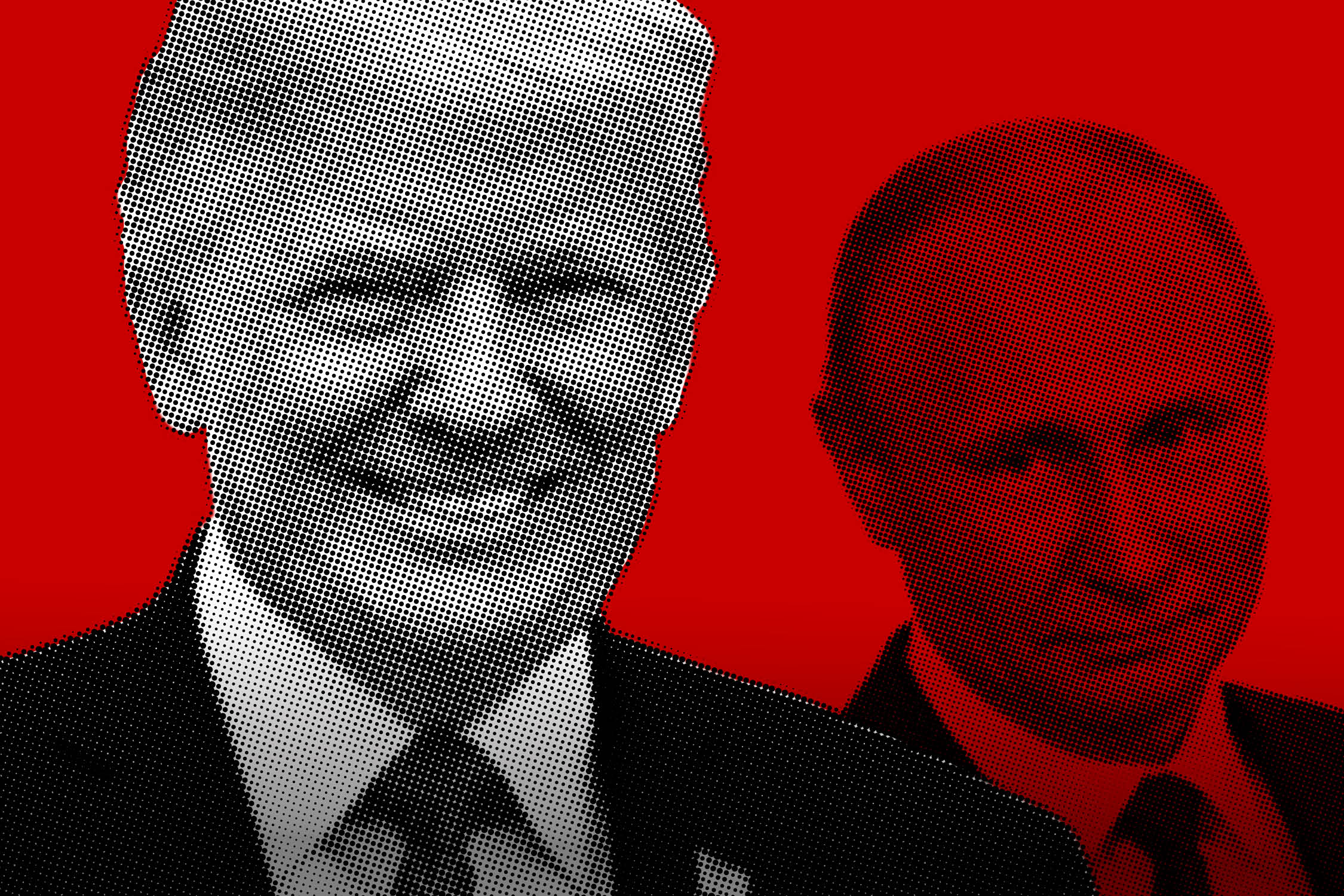

The problem now is that the U.S. has accused Russia of cheating. It’s alleged that Russian President Vladimir Putin has overseen the development and deployment of new missiles – such as the SSC-8, also known as the Novator 9M729 – that violate the agreement.

This is portrayed by the U.S. as a bid to intimidate Europe and former Soviet states allied to the West. Russia vehemently denies the allegations – although these protestations sound somewhat hollow after Putin gave a state of the nation speech last year announcing Russia’s new missile technology and even showing a video simulation of nuclear weapons hitting Florida.

Some in the U.S. welcome the withdrawal, saying ‘good riddance’ to the INF. Why should the U.S. commit to a treaty that Russia has broken? As Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said: ‘Russia has jeopardized United States security interests, and we can no longer be restricted by the treaty while Russia shamelessly violates it.’

But it is worth noting that the allegations against Russia are nothing new. The U.S. has voiced these accusations for five years, so why make a fuss now?

There are two reasons.

First: Withdrawal is political. The timing is extremely convenient for Trump. The president is currently under attack over his supposed collusion with Russia. The Mueller investigation has the White House in its crosshairs and it is no coincidence that the withdrawal statement comes just days after the arrest of controversial political consultant and lobbyist Roger Stone. Trump needs distance between himself and the Russians, and withdrawing from the INF sends the message that he is not Putin’s puppet.

Second: Withdrawal has less to do with being cheated on than Trump’s own plans for the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Trump has repeatedly said he wants new nuclear weapons technology. The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review was described a ‘list’ of new nuclear arms that Trump wants, including smaller nukes currently banned by the INF.

The details on this proposed new arsenal are still vague. It does not help that there are conflicting stories coming out of the White House as to whether withdrawal has anything to do with China: some say the move will allow the U.S. to develop new missiles to deter Beijing, but others insist this has nothing to do with the decision. It is clear, however, that Trump wants new missiles – even if his administration hasn’t got its story straight yet on why.

Withdrawal comes with serious consequences.

While some praise Trump’s hardline stance, this does not create a diplomatic climate in which fragile negotiations around nuclear weapons can take place. This is not just an issue concerning the INF, but also other nuclear reduction agreements such as new START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty). Moreover, to the extent that the INF may have at least curbed Russia’s behaviour in the past, it won’t now.

And if the U.S. uses this as an opportunity to develop new missiles, we could be looking at a new arms race.

It is not just diplomatic relations with Russia under threat.

The U.S. withdrawal has upset its European allies. The INF is very much a European issue: the limited range of the missiles involved means the U.S. homeland is not in the direct line of fire in the way that Europe is. This is not to say missile use in Europe is irrelevant to the U.S., but the INF does not have the same weight in Washington as it did during the Cold War. For Europe, however, this is a major concern and many feel the U.S. has thrown them under a bus. This will strain relationships, not only with individual countries in Europe but also in terms of NATO.

At present, the treaty is only suspended. Trump will serve a formal notice of withdrawal in six months time, and technically, this creates an opportunity to negotiate to maintain the INF.

But with Trump’s eyes very clearly on a shiny new nuclear arsenal and Mueller getting closer to the White House, this will be difficult to achieve.

Dr Michelle Bentley is Reader in International Relations and Director of the Centre of International Public Policy at Royal Holloway, University of London

All views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of The Defense Post.

The Defense Post aims to publish a wide range of high-quality opinion and analysis from a diverse array of people – do you want to send us yours? Click here to submit an Op-Ed.