What the end of the Qatar-Chad dispute means

On February 20, a joint statement between Qatar and Chad led to restoration of relations that had been under stress since June of last year.

Qatar has been under what it describes as an unjust “siege” since early June, when Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates broke diplomatic ties with the Gulf nation over its alleged ties to terrorist organizations and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Chad downgraded ties with Qatar in June and then took a step further.

Chad’s foreign minister Hissein Brahim Taha announced on August 23 the closure of the Qatari embassy in N’Djamena and ordered all Qatari diplomats out of the country. Chad accused Qatar of supporting Libya-based Chadian rebel groups bent on overthrowing its government. Qatar accused Chad of taking a bribe from the UAE.

“We are very concerned that Qatar is funding terrorists who wish to destabilize the government of Chad and it is possible, given our decision to break relations with Doha, that Qatar will increase its support for rebel groups,” said a Chadian intelligence figure who attended a gathering of Africa’s security services in Khartoum.

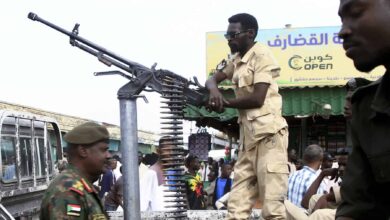

That announcement came days after “heavily armed militia” attacked a Chadian army patrol on the African nation’s northern border with Libya that Chad blamed on Qatar.

The Chadian press has also accused Qatar of sending cargo flights to resupply Chadian rebels in southern Libya. Qatar denies the allegations and has repeatedly denied any ties to terror groups in Africa.

One rebel group that concerns Chadian officials is the Front pour l’alternance et la Concorde au Tchad (FACT) which has clashed with both Libyan National Army and launched strikes into Chad.

Chad has also accused Qatar of funding and giving shelter to Chadian rebel leader Timane Erdimi who is allegedly living in Doha. Erdimi is also the nephew of the Chadian President Idriss Deby. Both are members of the important Zaghawa tribe whose roughly million members live along both sides of the 845 mile long Chad-Sudan border.

Since the turn of the millennium, the tribe’s allegiance has vacillated between both Khartoum and N’Djamena as the two capitals have sought for influence in the group. The tribe’s allegiance was at the heart of the civil wars in Chad and Darfur in the past decade. The conflict resulted in tensions between Sudan and Chad.

Those conflicts largely ended in 2010 when Chad and Sudan decided to stop their proxy strife with mediation and support from Doha. Since then the two countries have maintained a joint cross-border peacekeeping force that is innovative in the region.

“We have a very long border with the same tribes living on both sides which makes it easy for outside parties to use the situation to undermine the situation in Darfur,” says Mahdi Ibrahim Mohamed, a former Sudanese ambassador to the United States and government minister. “But, we have established good relations and joint military power across the border to close this line from being misused against both countries and we are working closely together.”

Chad and Sudan, the two countries whose rivalry fueled the war in Darfur a decade ago, found themselves on different sides of the Qatari diplomatic crisis.

“We don’t want our two countries to become pawns of great powers, and we have taken steps to prevent that,” Mohamed told The Defense Post.

The return of Chadian and Darfuri rebels fighting for various factions in Libya was discussed in a 2017 United Nations report focused on Libya. The return of those insurgents to the tri-border region shared by the three countries could lead to a new round of fighting in Darfur.

“There are 600 rebels from the Minnawi faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement who are fighting in Libya with General Haftar’s forces,” Sudan’s Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ghandour said in an interview with the author. “Those rebels could return anytime with support from Libya and re-ignite the war in Darfur.”

‘Scapegoat strategy’

Chad and Sudan also find their relationships with the U.S. headed in very different directions. The Trump administration put visa restrictions on Chad in September, and several days later removed sanctions on the Sudan which had been in place since 1997.

Experts say concerns that Chadian nationals could return from the Libyan conflict radicalized may have prompted their inclusion on Trump’s travel ban. Though the move was likely unintentional it was a severe blow to Chad’s rising prestige on the continent.

“Since its successful military interventions in Mali, Cameroon and CAR, the government of Chad is trying to raise its profile as a major security stakeholder on the continent,” Moudwe Daga, a Chadian international relations scholar based in London, told The Defense Post. “The culmination of which can be seen in the election of the Chadian foreign minister to the role of Chairperson of the African Union Commission.”

Daga also believes that the Qatari-Chad dispute was part of a “scapegoat strategy” that long-time Chadian President Idriss Deby employed to alleviate pressures on the regime.

“The Chadian government resorted to a similar strategy in 2008, when it referred to ‘armed bands and mercenaries’ in the pay of the government of Khartoum,” he said. “These accusations did not prevent the same government from later seeking a rapprochement with Khartoum when regime survival was at stake.”

After Trump’s designation, Chad removed its forces that had been fighting against Boko Haram terrorists in the border region it shares with neighboring Niger, although it is unclear whether the move was designed in response to Trump or rather as an effort to improve security at home in face of emerging threats. Chad also began pulling its peace-keeping force from the Central African Republic in 2014.

Instead Chadian troops have reportedly been deployed to neighboring Cameroon where they are involved in quelling Anglophone separatists in the south.

The joint statement last month makes no mention of the fate of Timane Erdimi, who is presumably still in exile in Doha, but both Chad and Qatar have committed to a fresh start to their relationship.